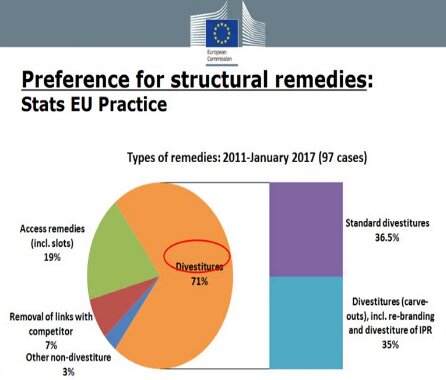

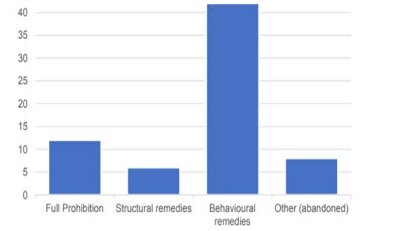

For most M&A deals that raise antitrust flags, remedies may appease regulators. While divestitures are the preferred option, especially in horizontal deals, behavioural remedies are widely used in vertical and conglomerate mergers.

EU regulators favoured divestitures as a clear-cut remedy capable of eliminating competition concerns entirely. This type of remedy will likely lead to a merger approval. A divestiture may include transferring all tangible and intangible assets (i.e. R&D, production, intellectual property rights), personnel, licenses, permits, contracts, leases, and customer records to a new company to ensure its viability and competitiveness. Sometimes a carve-out or a patent sale may be sufficient. Select M&A in which divestitures were required for clearance in Europe include Bayer-Monsanto, Tronox-Cristal, ArcelorMittal-Ilva and Honeywell-Elster

Access to key infrastructure, technology or the promise by the parties to abstain from certain commercial behavior (i.e. bundling, raise prices) may be an adequate solution in vertical M&A, but approval won’t be quick. This type of remedy is unlikely to be accepted for antitrust concerns resulting from horizontal overlaps. Non-divestiture remedies may be limited to 5-10 years, but are normally reviewed by EU regulators, which at any time may extend, modify or waive the remedies. Some M&A may require structural and behavioral remedies to eliminate all the antitrust concerns. Examples include Dow-Dupont, Qualcomm-NXP and Bayer-Monsanto.

If regulators identify a concern during the pre-notification talks, companies may offer remedies during the first 20 working days of the merger review and still get a phase-one approval. Only a divestiture seems to be a suitable remedy in a phase-one review. If concerns are found during a phase-two review, the companies should submit a remedy proposal within the first 65 working days. Companies are normally informed of the concerns in advance of the 65th day, and they don’t need to wait for a statement of objections. In UTC-Rockwell, the companies identified the antitrust concerns before filing the deal, and they proposed a divestiture remedy during the phase-one review, appeasing regulators and obtaining quick approval.

If divestitures are required for approval, companies have around six months from the merger decision to find a suitable buyer, or the regulator may order the divestiture trustee to sell the business at any price. Companies are advised to identify one or more possible suitor (“upfront buyers”) before concluding the merger review. In some instances, the companies and the buyer may even enter into a binding agreement before a decision is reached (“fix-it-first remedy”). Once a buyer is approved by the EU regulator, the parties normally have 3-6 months for closing