We are listening more and more often the word “ecosystem” to describe the numerous services that Internet giants are providing and how the are intertwined. In antitrust, we read it in the Google Android case, particularly, how Google leveraged its market power to protect the Android ecosystem.

This may not be a trivial word. Some people, and not only in the antitrust community, argue that Google, Facebook and others are not longer platforms but ecosystems and they are implicitly suggesting that markets should be widely defined. This new word fares well for Facebook as it is trying to move from the problematic (in antitrust terms) social network tag to a more dynamic and broader ecosystem tag.

Probably nobody questions that most of the services provided by these companies belong to different markets and they shouldn’t be mixed up in the same market definition. In this regard, social network, online marketplace, searches, payments, all are separate markets. Yet, it is difficult to figure out in which markets these companies will compete in the next 5 years, or as we suggest below, whether the companies’ ecosystems will compete with each other.

Alphabet’s self-driving car Waymo recently hit 10 million miles, way ahead of other competitors like Tesla or Uber. Thus, it is safe to assume that all these companies will compete in a foreseeable future.

Facebook is close to launch its own cryptocurrency, GlobalCoin in 2020. The company recently set up a new financial technology company in Switzerland focusing on blockchain and payments, LibraNetworks. In addition to pushing payments among Whatsapp users, Facebook wants to allow users to make payments anywhere in the world. This move will position Facebook as a potential or actual competitor of card processors and even banks.

These are just two examples of how market boundaries will be more blurred in the future. Then, two important concepts for antitrust purposes arise, ecosystems and consumers’ attention. These companies, specially Google and Facebook, rely heavily on online advertising revenues to cover the cost of their ecosystems. They need to constantly increase advertising revenues. For the time being, advertising volume grew year over year around 40% in avarage in the last quarters, but we already saw a decrease of around 13% in average in ad pricing for the last two quarters.

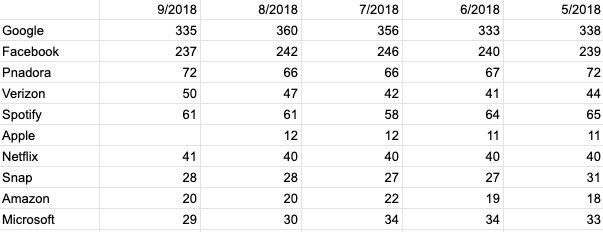

Consumers’ attention will be then paramount for them to keep revenues up as prices may go down. And this is where we start to see some changes. The U.S. and Europe are not mature markets yet, but the time spend per user in these platforms in 2018 has been relatively constant (sometimes even decreasing) for the last months. It is likely that Google, Facebook and Microsoft will compete fiercely for the limited number of hours that consumers may be stuck to their phones or computers (in another article we will talk how these companies will soon step up their fight in offline markets) and during that time, these companies will offer everything they have to keep consumers logged in. This means searches, payments, online banking, social interaction and online marketplaces will likely converge in one single company/site who will do anything to keep you surfing only in its website.

Source: Bloomberg

And now we come back where we started, should certain ecosystems be compared to each other as companies may compete for the same input (consumers’ attention)? or should each activity in the ecosystem be analyzed separately? The former seems to be the way firms operate but accepting this approach would have a clear impact on possible market definitions (i.e. harder to prove dominance). The latter is the way regulators have reviewed these markets so far but it may be difficult to sustain it in the long term as companies evolve.